To go along with the last post on welding myths and non-weldable materials, I also often get grudging calls from a designer who has been “forced” to add a weld to a design.

Customer: “How much do I have to overdesign this part for this weld?”

Me: “Why do you want to overdesign?”

Customer: “Well, the weld is going to weaken the part! I need to beef it up to compensate.”

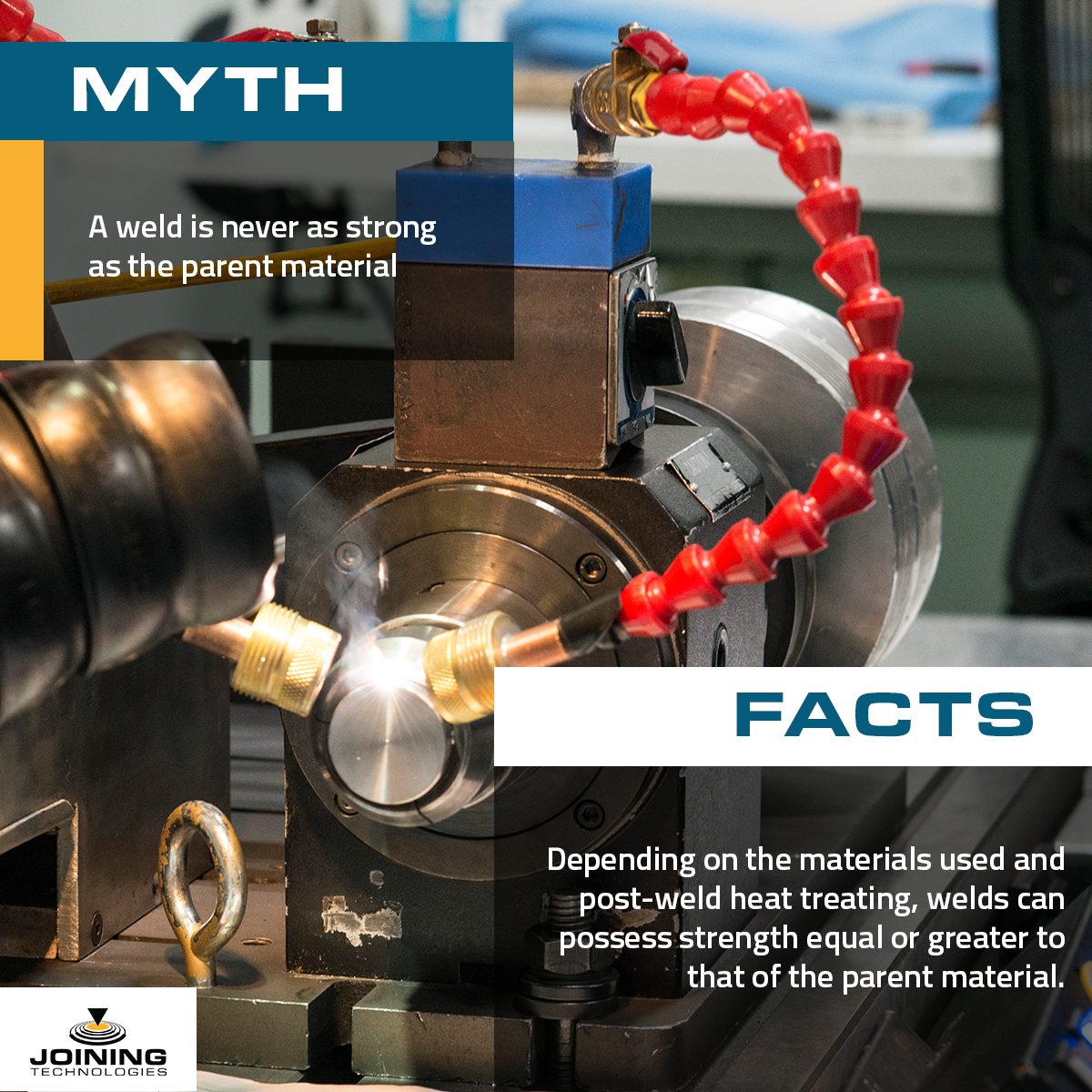

Au contraire. Weld strength, which by the way is an ambiguous term, is related to the parent material characteristics, part configuration and weld parameters. So, to refer back to welding myth #2 (If it’s metal, I can weld it), if Mr. Customer designed his part out of 303 stainless steel, the weld is indeed going to be weaker than the parent material and will be a failure point. However, that same part made from annealed 304L may actually be stronger at the weld. SURPRISE! Consider this welding myth busted.

Solutions for weld strength

It’s true that in many cases the weld will lead to softening or hardening of the material in the region in and adjacent to the weld, but very often this can be addressed by choosing a different material or by simply adding a post weld heat-treatment to restore characteristics to those of the parent material.

Quick example: Modern firearms are employing laser welding more and more frequently. However, they are often made from carbon and alloy steel, two materials that don’t always play well after welding. However, the proper heat treatment will make the difference between a part that will survive less than one hundred shots and one that will sustain tens of thousands of shots.

Don’t fall into the trap of believing that a weld will be the weakest point of your part. Always consult an expert and use welding to make you look like a hero on your next “impossible” design.